Recently I gave a talk to a group of young and aspiring engineers at Pursuit about getting their first job in technology. One of the questions they asked me was: “If someone for whom you cared deeply was one of the students and you could advise him or her only once, what would that key advice be?” Here is my answer.

If someone I cared about deeply were in the program and was aspiring to a career as a software engineer, I wouldn’t give him or her just one piece of advice. What my loved one would need to know and learn is far too complex to be reduced to just one pithy sentence. It would be a disservice to that person and a serious display of apathy if all I did was say one thing. No one thing anyone can say is so profound that it will change everything.

That said, let me try and reduce what I think would help you in your question to a few items.

Write a lot of code. And I mean a lot. You are in this program for just under a year or so. Write thousands of lines in the year you are part of the program and thousands more when you get out, whether professionally or for yourself. The code you write for the program counts, of course, but write more than that. Solve problems on HackerRank or LeetCode. Find an open source project. Come up with your own project. It doesn’t really matter why you write it, it just matters that you do.

The foundation of the ability I have today was the thousands upon thousands of lines of C and C++ I wrote when I was an undergraduate, either as part of my coursework (hundreds of lines) or a job (thousands) or just pursuing my own curiosity (thousands more).

There are no short cuts around this and there is no book, no web page, nor YouTube video that will absolve you of the need to churn out lines and lines of code. You just have to do it.

Production is what the marketplace rewards. Nothing less, nothing more. Never forget that someone is paying you to produce software. If someone is going to pay you, it’s because they want a product in return. Your success in any career will be always be a function of how much product you can deliver and at what quality. In your case, your product is software since you are aspiring to be software engineers. You have to deliver as much software as possible and at as high a quality as possible. This is why you need to start writing a lot of code. Now.

Your ability to produce is a function of your skill. “Skill” here means how well you know the programming language you were asked to use, how quickly you understand the problem you have been asked to solve, and how well you apply the language you know to the problem at hand. When you advance, “skill” will mean how well you design the solution in anticipation of problems because problems will become more general and vague and you will have to solve problems you have yet to experience. Later on, “skill” will mean choosing which language to use in the first place, which technologies to use and how to put them all together to build systems. As you advance in your career, you will produce larger and larger pieces of software.

Learn how to learn. The volume of information in the field of computer science is massive and continually growing. In my own career I’ve learned and used Python, Scala, Java, C++, C, Perl, Pascal, FORTRAN, BASIC. There’s Object-Oriented Design and Programming, Procedural Programming. Now with the popularity of massively parallel systems, there’s Functional Programming. Processes gave way to threads, single cores to multiple cores. Unix bred Linux, Windows actually became viable, NeXT became iOS. Waterfall moved on to Agile (supposedly).

You are going to have to learn a lot and in a very short period of time. This means you shouldn’t just be memorizing things. You need to get to the underlying principles beneath all that you are leaning—you need to get to first principles.

By the way, there is no such thing as a “preferred learning style”—the idea that some people are visual learners, some are auditory, some learn best by doing, some learn best listening. There is no scientific evidence for this.

There is the best way to learn given the domain, i.e., sometimes it’s best to read, sometimes it’s best to do, sometimes it’s best to watch and sometimes it’s best to listen. It depends on the subject, not the learner.

Embrace the frustration. The best sign that you are learning is that you are frustrated. If anything you are learning is too easy, you are not learning enough and you are not trying hard enough. If you find writing code easy, you are not challenging yourself enough. Embrace the suck.

Protect your most valuable asset for your career. Your most valuable asset an engineer is your brain. Take care of it. Train it to focus. Push it then let it get rest. Feed its hunger for knowledge through reading and other forms of intellectual exploration. Don’t let it get distracted by trifles. Sleep.

Learn how to build relationships! Engineers are notoriously bad at this but relationships are one of the foundations of your success—not to mention your overall happiness. This is nothing less and and nothing more than learning how to develop friendships with the people you will encounter in your career.

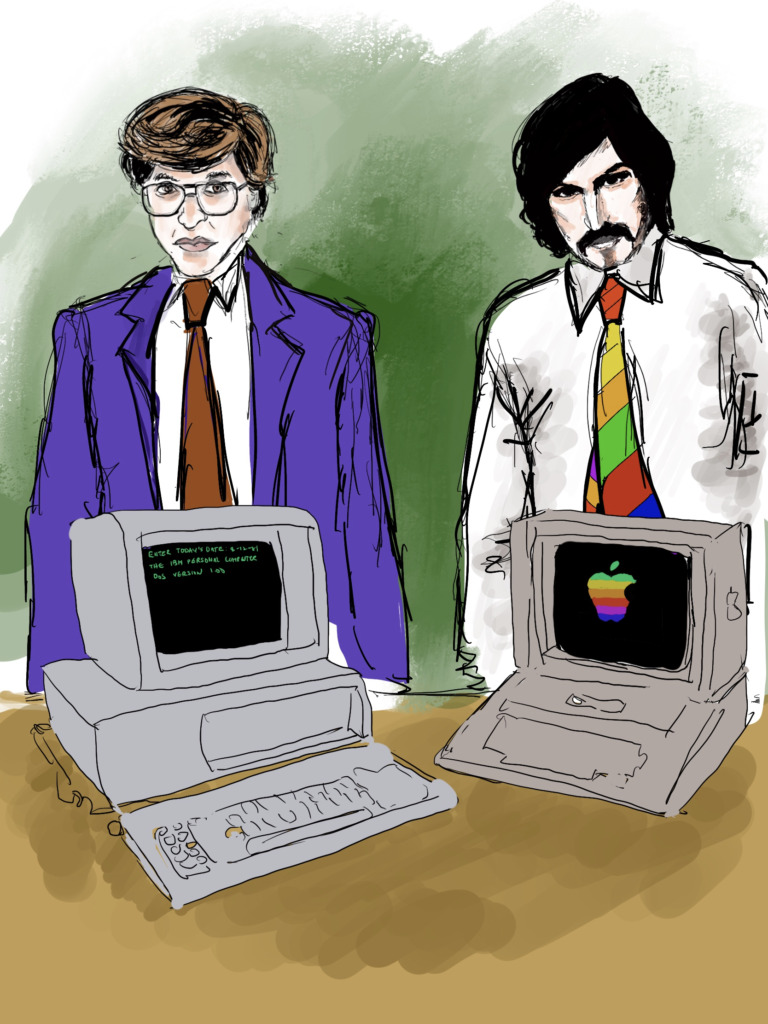

The quality of your relationships in your career as an engineer will dictate how much you learn, what opportunities you will see and what path you will take. Bill Gates needed Paul Allen. Steve Jobs needed Steve Wozniak. Larry Page needed Sergey Brin. All of them needed networks of people who believed in them and trusted them.

Building relationships is not the same as “networking”. I despise that word. It is utilitarian, insincere and not only is it useless, it is actually destructive.

You will need help from someone who has something you don’t in order to succeed—whether it is knowledge or access to opportunity—and if that person senses that you are “networking” with them, i.e., you are only trying to connect with them because they have something you need, it’s over—that person who has something you need will shut you down.

Networking is transactional—taking. Relationships are built on trust and generosity—sharing.

Have fun. There are few actions in life that bring as much joy to human beings as the act of creation. Ask any artist or author, movie director or screenwriter, mother or father. When you bring something new into this world it is deeply pleasurable. Writing code is an act of creation. A software engineer at his or her best is an artist, no less so than Picasso or Da Vinci. Yes, you must follow mathematically constrained rules, but that shouldn’t limit you, it should free you. The rules are the rules of logic and they are simply the canvas of your creation.

You’ll be frustrated and you’ll be infuriated but, in the end, if you are doing it right, you should be having fun.