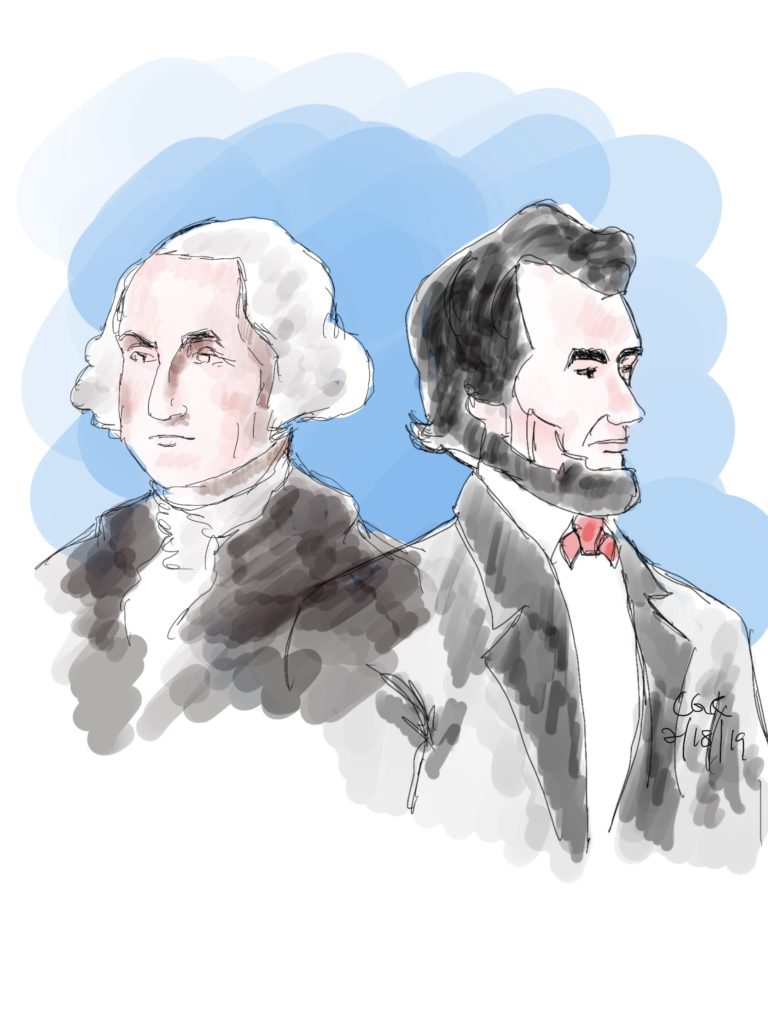

It is President’s Day in the United States, the day that Americans celebrate the birthdays of two of the greatest presidents in American history: George Washington, born February 22, 1732, the father of the nation and Abraham Lincoln, born February 12, 1809, the Great Emancipator and Rail Splitter.

There are many reasons each one has been deemed by history to be the two greatest (depending on the list, they often trade first and second place) but surely the scale of the problem each one faced contributed to these assessments. Washington had to bring forth a nation and a type of government that hadn’t existed on earth for nearly two thousand years. Lincoln had to keep that nation intact in the face of massive armed opposition. In other words, each President faced existential level threats.

Given the massive scale of he problems each one faced, what is of interest to me is how each man solved it. Entire volumes have been written about their respective solutions, of course (see The Glorious Cause and Battle Cry of Freedom). But for the sake of my study of problem solving a key step each man engaged is what interests me today on President’s Day: identifying and gathering your resources.

It should go without saying that neither man solved their respective existential level problems by themselves. Washington had to raise an army, train it, arm it and clothe it. Lincoln had so supply his army, identify how much of his army even remained after his inauguration, unify his allies, and gain support for the fundamental changes to the country and government his predecessor, Washington, had birthed. In other words, each man had to identify what resources he had available, gather them together, and bring them to bear.

On a much smaller scale, this is often the step we all tend to forget when we are faced with a crisis or a problem. In a moment of panic we might actually forget what we know. We might not remember what we actually have or who is actually on our side because we are so wrapped up in the scale of the problem instead in the promise of the opportunity. Hell, that just happened to me today. And it tends to happen to my students when faced when a seemingly inscrutable problem on a test. They forget how much they know. They forget just how smart and how talented they actually are, just as you (and I) often do when under pressure and confronted with a threat.

So that’s the next step in problem solving: Identify and Gather Your Resources.

How to Solve Any Problem:

Step 1: Get Your Mind Right

Step 2: Identify and Clarify the Problem

Step 3: Break It Down

Step 4: Identify and Gather Your Resources